March 7th: Today’s Feature

- webbworks333

- Mar 7, 2025

- 5 min read

March

Part 1

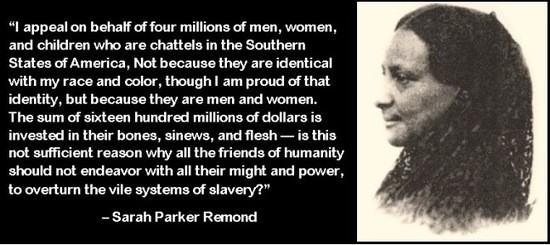

Sarah Parker Remond (June 6, 1826 – December 13, 1894) was an American lecturer, activist and abolitionist campaigner.

Born a free woman in the state of Massachusetts, she became an international activist for human rights and women's suffrage. Remond made her first public speech against the institution of slavery when she was 16 years old, and delivered abolitionist speeches throughout the northeastern United States. One of her brothers, Charles Lenox Remond, became known as an orator and they occasionally toured together for their abolitionist lectures.

Eventually becoming an agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society, in 1858 Remond chose to travel to Britain to gather support for the growing abolitionist cause in the United States. While in London, Remond also studied at Bedford College, lecturing during term breaks. During the American Civil War, she appealed for support among the British public for the Union and their blockade of the Confederacy. After the conclusion of the war in favour of the Union, she appealed for funds to support the millions of the newly emancipated freedmen in the American South.

From England, Remond went to Italy in 1867 to pursue medical training in Florence, where she became a physician. She practiced medicine for nearly 20 years in Italy and never returned to the United States, dying in Rome at the age of 68.

Early Years

Born in Salem, Massachusetts, Remond was one of the between eight and 11 children of John Remond and Nancy (née Lenox) Remond. Nancy was born in Newton, daughter of Cornelius Lenox, a Revolutionary War veteran who had fought in the Continental Army, and Susanna Perry. John Remond was a free person of colour who immigrated to Massachusetts from the Dutch colony of Curaçao as a 10-year-old child in 1798. John and Nancy married in October 1807, in the African Baptist Church in Boston. In Salem, they built a successful catering, provisioning, and hairdressing business, becoming well-established businesspeople and activists.

The Remonds tried to place their children in a private school, but they were rejected because of their race. When Sarah Remond and her sisters were accepted to a local high school for girls which was not segregated, they were expelled, as the school committee was planning to found a separate school for African-American children. Remond later described the incident as engraved in her heart "like the scarlet letter of Hester."

In 1835, the Remond family moved to Newport, Rhode Island, where they hoped to find a less racist environment in which to educate their children. However, the schools refused to accept black students. Instead, some influential African Americans established a private school, where Remond was educated.

In 1841, the Remond family returned to Salem. Sarah Remond continued her education on her own, attending concerts and lectures, and reading widely in books, pamphlets and newspapers borrowed from friends, or purchased from the anti-slavery society of her community, which sold many inexpensive titles. The Remond family also took in as boarders students who were attending the local girls' academy, including Charlotte Forten (later Grimké).

Three of Remond's sisters built a business together: Cecilia (married to James Babcock), Maritchie Juan, and Caroline (married to Joseph Putnam),"owned the fashionable Ladies Hair Work Salon" in Salem, as well as the biggest wig factory in the state.Their oldest sister Nancy married James Shearman, an oyster dealer. The Remond brothers were Charles Remond, who became an abolitionist and orator; and John Remond, who married Ruth Rice, one of two women elected to the finance committee of the 1859 New England Coloured Citizens' Convention.

Anti-slavery Activism and Lecturing

Salem in the 1840s was a centre of anti-slavery activity, and the whole family was committed to the rising abolitionist movement in the United States. The Remonds' home was a haven for black and white abolitionists, and they hosted many of the movement's leaders, including William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips, and more than one fugitive slave fleeing north to freedom.

John Remond was a life member of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society Sarah Remond's older brother Charles Lenox Remond was the first black lecturer of the American Anti-Slavery Society's and considered a leading black abolitionist. Nancy Remond was one of the founders of the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society. Nancy not only taught her daughters the household skills of cooking and sewing but also to seek liberty lawfully; she wanted them to take part in society.

With her mother and sisters, Sarah Remond was an active member of the state and county female anti-slavery societies, including the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, the New England Anti-Slavery Society, and the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. She also regularly attended antislavery lectures in Salem and Boston.

With the support and financial backing of her family, Sarah Remond became an anti-slavery lecturer, delivering her first lecture against slavery at the age of 16, with her brother Charles in Groton, Massachusetts, in July 1842.

Remond rose to prominence among abolitionists in 1853, when she refused to sit in a segregated theatre section. She had bought tickets by post for herself and a group of friends, including historian William C. Nell, to the popular opera, Don Pasquale, at the Howard Athenaeum in Boston. When they arrived at the theatre, Remond was shown to segregated seating. After refusing to accept it, she was forced to leave the theatre and pushed down some stairs.

Remond sued for damages and won her case. She was awarded $500, and an admission by theatre management that she was wronged; the court ordered the theatre to integrate all seating.

In 1856, the American Anti-Slavery Society hired a team of lecturers, including Remond; Charles, already well known in the U.S. and Britain; and Susan B. Anthony, to tour New York State addressing anti-slavery issues. Over the next two years, she, her brother, and others also spoke in New York, Massachusetts, Ohio, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

She and other African Americans were often given poor accommodation due to racial discrimination. Although inexperienced, Remond rapidly became an effective speaker. William Lloyd Garrison praised her "calm, dignified manner, her winning personal appearance and her earnest appeals to the conscience and the heart." Sarah Clay wrote that Remond's every word "waked up dormant aspirations which would vibrate through the ages." Over time, she became one of the society's most persuasive and powerful lecturers. Abby Kelley Foster, a noted abolitionist in Massachusetts, encouraged Remond when they toured together in 1857.

On December 28, 1858, Remond wrote in a letter to Foster:I feel almost sure I never should have made the attempt but for the words of encouragement I received from you. Although my heart was in the work, I felt that I was in need of a good English education ... When I consider that the only reason why I did not obtain what I so much desired was because I was the possessor of an unpopular complexion, it adds to my discomfort.