March 23rd: Today’s Feature

- webbworks333

- Mar 23, 2025

- 4 min read

March

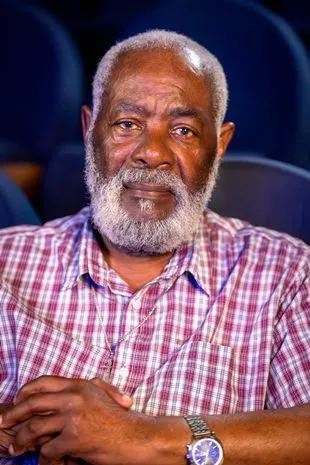

Guy Reid-Bailey, OBE - Part 2

The then manager of the Bristol Omnibus Company, Ian Patey, told Reid-Bailey that he “couldn’t employ blacks”. Later that evening, Reid-Bailey reported the news to Stephenson at the youth club, and the following day both went back to the bus company to protest. But Patey refused to bend, and the Transport and General Workers Union sided with the bus company. Soon, Reid-Bailey’s personal disappointment was transformed into a months-long boycott involving the Caribbean community, leading politicians and supporters – an initiative that ended the colour bar on Bristol’s buses. Reid-Bailey also credits the mobilisation for bringing about the 1965 Race Relations Act, which marked the beginning of the outlawing of racial discrimination in the UK.

Despite being involved in the protest, Reid-Bailey never worked on the buses. He did a short stint as a mental health nurse before getting a job working for the British Aircraft Corporation building parts for Concorde. He remembers his father’s dreams that he would become a lawyer or a doctor, and although he never got that opportunity, he is proud that he persevered and completed a social work degree at Bristol Polytechnic in the 80s and worked as an education and welfare officer for 20 years. His two sons and three daughters all went to university, too, and are what he calls “professional people”.

His education had to be pursued in evening classes because, when he moved to the UK, he says, it was compulsory for those arriving to register for work at age 16. The school he attended offered instruction in English, maths and history but not, he says, in the subjects he needed most. “I had to do my own research after I found out the life I was going to have. I had to find out a lot about what is known as Great Britain.” In other words, he was taught nothing about Britain’s empire or the Commonwealth, nor told anything that would instil pride in black history and help sustain him against the barrage of discrimination he faced.

Half a century later, he is frustrated that so little has changed. “I would like to see the schools teach black history and other history. How England become the world manager, the head of the Commonwealth. Those things are not being taught in school and they should be, so that younger people can understand when a black person says they are not being treated the same as white people.”

What kept him going was sport. “I used cricket as a sword, a weapon to show I could be as good as anyone else,” he says. After experiencing frustration at traditional clubs, which he felt were favouring white players, Reid-Bailey took matters into his own hands by helping to found the Bristol West Indies Cricket Club (BWICC) in 1963.

It was by no means easy. Some clubs initially refused to play against them. Reid-Bailey recalls that “one club in Bristol wouldn’t offer us a fixture until we played a trial game to show them we were good enough. We beat them so badly, they had to play us.” The club rapidly became one the best in the west of England. They were so successful that the local newspaper reported on their games, and when they travelled to play other clubs they were joined by up to six coachloads of their followers. Cricket was at the centre of Caribbean community life until the 90s, given focus by the fact that from the 70s onwards, the West Indies were the best team in the world.

“Cricket was the only thing we could hold on to,” says Reid-Bailey. “It helped us be seen as a force to reckon with, and it was something we could actually say was ours.” The success of the BWICC and others like it was something the whole community took pride in. The club still exists today. It joined with another local team to form the Bristol West Indian Phoenix Cricket Club, and is based at the Rose Green Centre, which Reid-Bailey helped raise funds to build. He is extremely proud that the club is still providing facilities and programmes for young people from ethnic minorities in the area.

Reid-Bailey’s commitment to the community remains undiminished. He is still involved with the cricket club and the housing association, attending meetings and offering advice. He describes his 30 hours a week working with unaccompanied asylum seekers and young people with issues at home for the housing association and social enterprise Riverside as “part-time”. Covid-19 may have trapped him indoors, but there is no sign of him letting up.

The Black Lives Matter protests have energised him because “they have opened the eyes of a lot of people who were hiding behind race equality. Over 50-odd years in England, I have been waiting to see the sort of changes that Black Lives Matter has brought about. It has established the strength of how people feel about racism and provided a way forward. I am more hopeful that things can change.”