October 29th: Today's Feature - British Army drops colour bar 1966

- webbworks333

- Oct 29, 2025

- 4 min read

October

British Army drops colour bar 1966

In the United Kingdom, racial segregation occurred in pubs, workplaces, shops and other commercial premises, which operated a colour bar where non-white customers were banned from using certain rooms and facilities. Segregation also operated in the 20th century in certain professions, in housing[ and at Buckingham Palace. There were no British laws requiring racial segregation, but until 1965, there were no laws prohibiting racial segregation either.

The colour bar, according to author Sathnam Sanghera, was an import from the British Empire, where people living under British rule would be segregated depending on their race and colour.

The colour bar in pubs was deemed illegal by the Race Relations Act 1965, but other institutions such as members' clubs could still bar people because of their race until a few years later. Some resisted the law such as in the Dartmouth Arms in Forest Hill or the George in Lambeth which still refused to serve non-white people on the grounds of colour.

World War II

The colour bar was experienced by segregated African-American allied troops stationed in the UK during the Second World War who were ordered by their superiors to not visit various pubs and social facilities. Some British pubs refused to comply with this segregation, such as in Bamber Bridge. Non-white British troops also faced a colour bar among private businesses, with instances of members of the Home Guard being refused entry to establishments even when wearing uniform.

Cabinet decision

In October 1942 the Cabinet (Churchill war ministry) discussed colour bars after Lord Cranbourne (actually Viscount Cranbourne) said that one of his black officials in the Colonial Office had been barred by a restaurant because American officers had imposed a “whites-only” policy.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill addressed the Cabinet (after making an insensitive joke; saying That’s alright, if he takes a banjo with him, they’ll think he’s one of the band) and Cabinet concluded that the US Army must not expect our authorities, civil or military, to assist them in enforcing a policy of segregation. It was clear that, so far as concerned admission to canteens, public houses, theatres, cinemas, and so forth, there would, and must not, be no restriction of the facilities hitherto extended to coloured persons as a result of the arrival of United States troops in this country.

Women's Land Army

In 1943, during the Second World War, Amelia King was refused work with the Women's Land Army on the basis of her colour. The decision was overturned after being raised in the House of Commons by her MP, Walter Edwards.

Amelia King - Women's Land Army

The British Army – A LEGACY OF VALOUR

Written by Lt Col Tim Petransky

11/11/2020

Black History Month 2018 coincides with the 100th anniversary of the Armistice; a fitting time to reflect on the contribution of the heroic and inspirational deeds of Afro-Caribbean soldiers to Britain.

As Armed Forces we champion recognition of the service of black servicemen and women and people from the Commonwealth and ethnic minorities.

These examples are select but highlight the contribution of Afro-Caribbean’s, underlining our shared heritage. They exemplify determination, professionalism, commitment and loyalty.

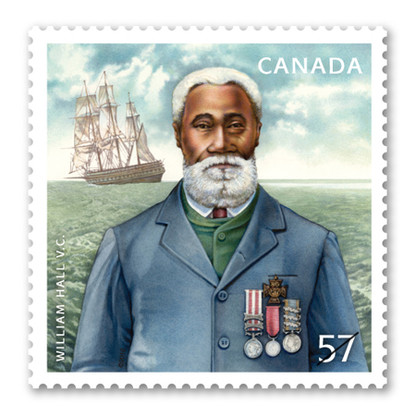

The Victoria Cross (VC), the Armed Forces’ highest award for valour, has been awarded to four Afro-Caribbean service personnel. First in 1857, William Hall of the Navy, most recently Sergeant Johnson Beharry, from Grenada, in 2004.

The first black soldier to win a VC was Samuel Hodge from the British Virgin Islands in 1866. Under fierce enemy fire, he hacked his way into a stockade where he Hodge and his Commanding Officer Colonel D’Arcy forced the gates, allowing its capture. D’Arcy cited Hodge “the bravest soldier in the Regiment.”

William Hall Sergeant Johnson Beharry

Hodge was seriously wounded in the action. Our medics who apply life-saving treatment to the injured, often under fire, are the embodiment of courage and selfless commitment. In this mould were Major James Africanus Beale Horton and Mary Seacole.

Horton, born to freed slaves in Sierra Leone in 1835, qualified as a doctor in Britain. He joined the Army as an Assistant Surgeon, one of the first Africans in the officer corps, participating in several wars.

Army service helped him develop important medical theories, earning him acclaim and promotion. He is held as the Father of modern African political thought writing pioneering works to rebut ideas of scientific racism.

Seacole supported the Army during the Crimean War from a sense of service to the wounded. Born in Jamaica in 1805 she achieved much before following the Army to Crimea in 1854.

Here she set up an establishment caring for wounded soldiers, travelling to battlefields on several occasions to tend casualties and was nicknamed ‘Mother Seacole’ by soldiers for her compassion. Seacole is commemorated by a statue outside St Thomas’ Hospital.

Walter Tull, a true role model, demonstrated patience, humility, fortitude and bravery, enduring racism and hardship but came out on top. A professional football player before World War One he joined the Army in 1914.

Despite prevailing attitudes, his ability and strength of example saw him selected as an officer, the first black man to lead white troops. He was mentioned in dispatches for bravery but was killed on the 8 March 1918.

These examples illustrate the valuable contribution of Caribbean and African people to the Army, even more remarkable considering the barriers they faced. The modern Army aspires to represent the society it serves.

Diversity is a strength in today’s complex world and closely aligns to two of the Army’s core values: Respect for Others and Integrity. Serving today are people from many different ethnicities and colours who can be proud of their illustrious forebears, who would be immensely proud of them.

Ref: