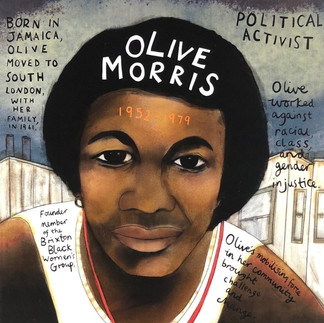

November 5th: Today's Feature - Olive Morris, Activist, Feminist, Squatters Rights Campaigner & Community Leader

- webbworks333

- Nov 5, 2025

- 5 min read

November

Olive Elaine Morris - Part 1

(26 June 1952 – 12 July 1979) was a Jamaican-born British-based community leader and activist in the feminist, black nationalist, and squatters' rights campaigns of the 1970s. At the age of 17, she was assaulted by Metropolitan Police officers following an incident involving a Nigerian diplomat in Brixton, South London.

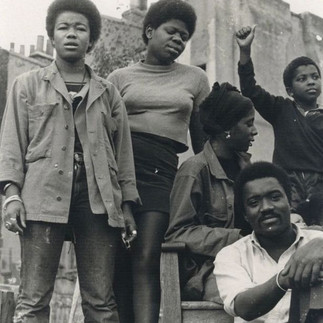

She joined the British Black Panthers, becoming a Marxist–Leninist communist and a radical feminist. She squatted buildings on Railton Road in Brixton; one hosted Sabarr Books and later became the 121 Centre, another was used as offices by the Race Today collective. Morris became a key organiser in the Black Women's Movement in the United Kingdom, co-founding the Brixton Black Women's Group and the Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent in London.

121 Railton Rd & 165-167 Railton Rd where Race Today was produced

When she studied at the Victoria University of Manchester, her activism continued. She was involved in the Manchester Black Women's Co-operative and travelled to China with the Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding. After graduating, Morris returned to Brixton and worked at the Brixton Community Law Centre.

She became ill and received a diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. She died at the age of 27. Her life and work have been commemorated both by official organisations – Lambeth Council named a building after her – and by the activist group the Remembering Olive Collective (ROC). Friends and comrades recalled her as fearless and dedicated to fighting oppression on all levels. She was depicted on the B£1 note of the Brixton Pound and has featured on lists of inspirational black British women.

Early life

Olive Morris was born on 26 June 1952 in Harewood, St Catherine, Jamaica. Her parents were Vincent Nathaniel Morris and Doris Lowena (née Moseley), and she had five siblings. When her parents moved to England, she lived with her grandmother and then followed them to South London at the age of nine.

Her father was employed as a forklift driver and her mother worked in factories. Morris went to Heathbrook Primary School, Lavender Hill Girls' Secondary School, and Dick Sheppard School in Tulse Hill, leaving without qualifications. She later studied for O-Levels and A-levels, and attended a class at the London College of Printing (now named the London College of Communication).

Adult life and activism

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, black British activists embraced the multi-ethnic political discussions concerning black nationalism, classism and imperialism in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean, as well as in the United Kingdom. Their overriding goals were to find their identity, cultural expression and political autonomy by helping their own communities, and others with similar struggles.

Despite the passage of the Race Relations Act 1965, Afro-Caribbean people (alongside other minority groups) continued to experience racism; access to housing and employment was restricted in discriminatory ways and black communities were put under pressure by both the police and fascist groups such as the National Front.

To combat these issues, black Britons used anti-colonial strategies and adopted African-inspired forms of cultural expression, drawing on black power movements, or black liberation movements in Angola, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique and Zimbabwe. Similarly, black British activists challenged ideas of respectability by the choices they made for their adornment, clothing, and hair styles.

They listened to reggae and soca from the Caribbean and soul from the United States, and displayed images of internationally known revolutionary figures, such as Che Guevara and Angela Davis. Their fashion sense was also influenced by the civil rights movement.

Morris was drawn into this movement because it allowed her to affirm her Caribbean roots and blackness, while also providing a means for her to fight against problems affecting her community. Just over five feet tall, she gained a reputation as a fierce activist.

She was described by other activists as fearless and dedicated, refusing to stand by and allow injustice to occur. Oumou Longley, a gender studies and black history researcher, notes that Morris's identity was complex: "A Jamaican-born woman who grew up in Britain, a squatter with a degree from Manchester University, a woman with a long-term white-skinned partner and a woman who during this time had intimate relationships with other men and women".

She deliberately appeared androgynous, adopting a "queer revolutionary soul sister look”. Morris smoked, preferred jeans and T-shirts, either went bare-footed or wore comfortable shoes, and wore her hair in a short-cropped Afro. Her personal style choices challenged not only notions of what it meant to be British, but also Caribbean.

African-American scholar Tanisha C. Ford observes that Morris was gender-nonconforming in the same way as the activists of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the US, who cut their hair short and switched from wearing dresses and pearls to overalls.

Mistreatment following the Gomwalk incident

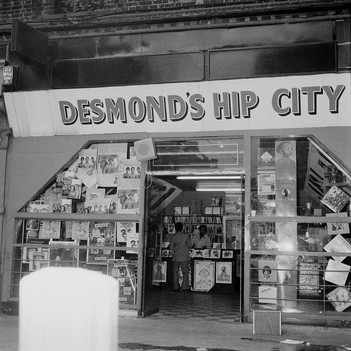

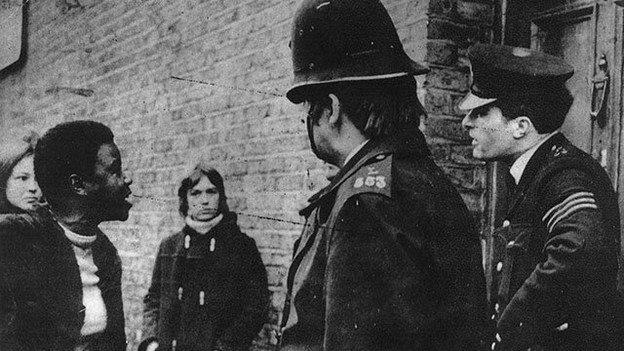

On 15 November 1969, Nigerian diplomat Clement Gomwalk was confronted by Metropolitan Police officers while parked outside Desmond's Hip City, the first black record shop in Brixton.

The Mercedes-Benz car he was driving bore a different number on the licence plate to that on the licence disc; police officers pulled him from the car and questioned him under the "sus law" (a stop and search power), disputing that he was a diplomat.

A crowd formed around them and then a physical altercation took place. Local journalist Ayo Martin Tajo wrote up an account of the events a decade later which stated that Morris pushed through the crowd and attempted to stop the police hitting the diplomat; this led to the police assaulting her and several others.

On Morris's own account as published in the Black People's News Service (the newsletter of the British Black Panthers), she arrived after Gomwalk had been arrested and taken away in a police van.

The situation with the police officers escalated after the crowd began to confront them about their brutal treatment of Gomwalk. Morris recalled her friend being dragged away by police, shouting "I've done nothing" as his arm was broken. She did not relate exactly how she became involved, but did record that she was arrested and later beaten in police custody.

Since she was dressed in men's clothing and had very short hair, the police believed she was a young man, one of them saying "She ain't no girl". According to Morris' account, she was forced to strip and threatened with rape: "They all made me take off my jumper and my bra in front of them to show I was a girl.

A male cop holding a billy club said, 'Now prove you're a real woman.'" Referencing his club (truncheon or baton), he stated: "Look it's the right colour and the right size for you. Black c**t!" Morris's brother Basil described her injuries from the incident, saying that he "could hardly recognize her face, they beat her so badly".

She was fined £10 and given a three-year suspended sentence of three months in prison for assaulting a police officer; the term was later reduced to one year. This was a formative experience for Morris, who became a Marxist–Leninist communist and a radical feminist. Her politics were intersectional, focusing on racism worldwide whilst aware of the connections to colonialism, sexism and class discrimination.