November 6th: Today's Feature - PART II: Olive Morris & the British Black Panthers

- webbworks333

- Nov 6, 2025

- 5 min read

November

PART II: Olive Morris

British Black Panthers

Morris decided to campaign against police harassment and joined the youth section of the British Black Panthers at the beginning of the 1970s. The group was not affiliated with the Black Panther Movement in the United States, but shared its focus on improving local communities. The British Panthers promoted Black Power and were pan-African, black nationalist and Marxist-Leninist.

Morris was introduced to Altheia Jones-LeCointe, Farrukh Dhondy and Linton Kwesi Johnson and in August 1972, she attempted to meet Eldridge Cleaver, a leader of the US movement, in Algeria; travelling with her friend Liz Obi, she only made it as far as Morocco. They ran out of money and had to ask at the British consulate in Tangier for help to return home.

In the early 1970s, there were many court cases involving black activists on trumped up charges. At the trial of the Mangrove Nine, the Black Panthers organised solidarity pickets; the accused were eventually found not guilty, the judge acknowledging that officers of the Metropolitan Police were racially prejudiced.

During the trial of the Oval Four, Morris was arrested after a scuffle with police officers outside the Old Bailey alongside Darcus Howe and another person. The three were charged with assault occasioning actual bodily harm and took a political approach to their subsequent trial, requesting that members of the jury were either black, working-class or both.

They researched the background of the judge, John Fitzgerald Marnan, and discovered that as Crown counsel in Kenya he had prosecuted participants in the anti-colonial Mau Mau Uprising.

When the case came to trial in October 1972, the nine police officers gave contradictory evidence, including about the footwear Morris had been wearing, a crucial point since she was accused of kicking an officer. The jury acquitted her and the other defendants.

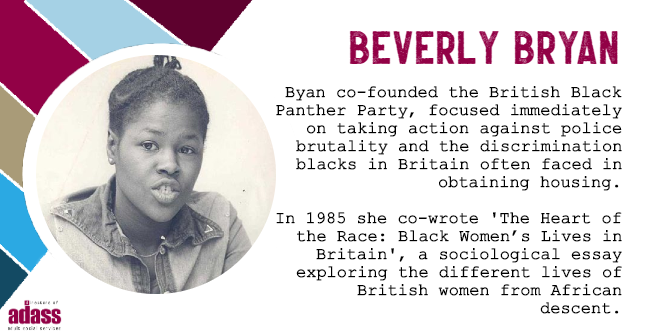

Upon the demise of the British Black Panthers, Morris founded the Brixton Black Women's Group with Obi and Beverley Bryan in 1973. The collective explored the experience of women in the Black Panther Party and aimed to provide a space for Asian and black women to discuss political and cultural matters more generally.

It was critical of white feminism, finding that issues such as abortion and wages for housework were not central to the black experience, since participants were more concerned about childcare and getting paid for their cleaning jobs.

The group was organised non-hierarchically; it published the newsletter Speak Out and produced The Heart of the Race: Black Women's Lives in Britain, which was published by Virago Press in 1985. Three women from the collective were credited as authors because the publisher refused to use a collective name. Dedicated to Morris, the book was republished by Verso Books in 2018.

Squatting in Brixton

Having begun to squat buildings in Brixton on account of housing need, Morris came to see occupation as a means to establish political projects. Squatting provided a way for the Brixton Black Women's Group to remain autonomous from the broader women's liberation movement in England.

In 1973, Morris squatted 121 Railton Road with Liz Obi. When workers broke in and took away their belongings, Morris and Obi quickly re-squatted the house and made a deal with the estate agent. Speaking to the London daily newspaper The Evening Standard, Morris said "the prices for flats and bedsits are too high for me".

The Advisory Service for Squatters used a photograph of Morris climbing up the back wall of the squat on the cover of its 1979 Squatters Handbook. The building became a hub of political activism, hosting community groups such as Black People against State Harassment and the Brixton Black Women's Group.

Sabarr Bookshop was set up by a group of local black men and women that included Morris and through it, activists were able to work with schools to provide black history reading materials for a more diverse curriculum. Morris and Obi then moved on to another squat at 65 Railton Road.

The 121 squat later became an anarchist self-managed social centre known as the 121 Centre, which existed until 1999. Anthropologist Faye V. Harrison lived with Morris and her sister in the mid-1970s; she later recalled that Morris saw housing as a human right and squatting as direct action to provide shelter, so she was keen to encourage other people to squat.

Morris was also involved with the Race Today collective, which featured Farrukh Dhondy, Leila Hassan, Darcus Howe and Gus John. When it split from the Institute of Race Relations in 1974, she helped it find a base in the squats of Brixton. The offices were eventually located at 165–167 Railton Road, where the collective produced the magazine and held discussion sessions in the basement.

165-167 Railton Rd

C. L. R. James lived on the top floor of the building. The offices later became the Brixton Advice Centre.

Manchester

Morris studied economics and social science at the Victoria University of Manchester from 1975 until 1978. She quickly integrated with grassroots political organisations in Moss Side, co-founding the Black Women's Mutual Aid Group and meeting local activists such as Kath Locke and Elouise Edwards. Locke had set up the Manchester Black Women's Co-operative (MBWC) in 1975 with Coca Clarke and Ada Phillips; Morris got involved and members later recalled her vigour.

She also campaigned against the university's plans to increase tuition fees for overseas students. After her death, the MWBC folded due to financial mismanagement and reformed as the Abasindi Women's Co-operative; from its base in the Moss Side People's Centre, Abasindi organised educational, cultural and political activities without any public funding.

Morris helped to establish a supplementary school after campaigning with local black parents for better education provision for their children, and a black bookshop. As part of her internationalist perspective she participated in the National Co-ordinating Committee of Overseas Students and travelled to Italy and Northern Ireland.

In 1977, she travelled to China with the Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding and wrote "A Sister’s Visit to China" for the newsletter of the Brixton Black Women's Group. The article analysed anti-imperialist praxis and community organisation in China.

Return to Brixton

After graduating in 1978, Morris returned to Brixton and worked at the Brixton Community Law Centre. With her partner Mike McColgan she wrote "Has the Anti-Nazi League got it right on racism?" for the Brixton Ad-Hoc Committee against Police Repression. The pamphlet questioned whether the Anti-Nazi League was correct to fight fascism whilst ignoring institutional racism.

Dadzie, Scafe & Bryan: Back then & more recently

With educationalists Beverley Bryan and Stella Dadzie, plus other women, Morris set up the Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent (OWAAD) in London. It held its first conference at the Abeng Centre in Brixton, which Morris had helped to found. Bryan later remembered Morris as a "strong personality”.

At the conference, 300 African, Asian and Caribbean women from cities including Birmingham, Brighton, Bristol, Leeds, London, Manchester and Sheffield came together to discuss issues that concerned them, such as housing, employment, health and education. OWAAD aimed to be an umbrella group linking struggles and empowering women, whilst also opposing racism, sexism and other forms of oppression.

Alongside the Brixton Black Women's Group, OWAAD was one of the first organisations for black women in the United Kingdom. Morris edited FOWAD!, the group's newsletter, which continued to publish after her death.

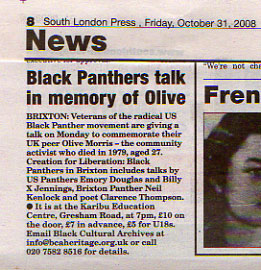

Death

Whilst on a cycling trip in Spain with McColgan in 1978, Morris began to feel ill. Upon her return to London, she went to King's College Hospital and was sent away with tablets for flatulence, only to later receive a diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in September. The cancer treatment was unsuccessful and she died on 12 July 1979 at St Thomas' Hospital, Lambeth, at the age of 27. Her grave is at Streatham Vale Cemetery.