November 17th: Today's Feature - Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Composer & Conductor

- webbworks333

- Nov 17, 2025

- 6 min read

November

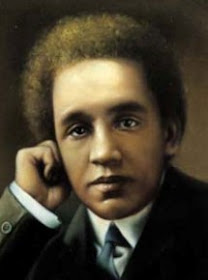

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (15 August 1875 – 1 September 1912) was a British-Sierra Leonean composer and conductor. Of mixed-heritage, Coleridge-Taylor achieved such success that he was referred to by white New York musicians as the "African Mahler" when he had three tours of the United States in the early 1900s. He was particularly known for his three cantatas on the epic 1855 poem The Song of Hiawatha by American Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Coleridge-Taylor premiered the first section in 1898, when he was 23.

He married a British woman, Jessie Walmisley, and both their children had musical careers. Their son Hiawatha adapted his father's music for a variety of performances. Their daughter Avril Coleridge-Taylor became a composer-conductor.

Early Life and Education: Coleridge-Taylor c. 1893

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was born at 15 Theobalds Road in Holborn, London, to Alice Hare Martin (1856–1953), an Englishwoman, and Daniel Peter Hughes Taylor, a Krio man from Sierra Leone who had studied medicine in London and later became an administrator in West Africa.

They were not married, and Daniel had returned to Africa without learning that Alice was pregnant. (Alice's parents had not been married at her birth, either.) Alice named her son Samuel Coleridge Taylor (without a hyphen), after the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Alice lived with her father, Benjamin Holmans, and his family after Samuel was born. Holmans was a skilled farrier and was married to a woman who was not Alice's mother, with whom he had four daughters and at least one son. Alice and her father called her son Coleridge. In 1887 she married George Evans, a railway worker, and lived in Croydon on a street adjoining the railway line.

There were numerous musicians on Taylor's mother's side, and her father played the violin, teaching it to his grandson from an early age. Taylor's musical ability quickly became apparent, and his grandfather paid for him to have violin lessons.

The extended family arranged for Taylor to study at the Royal College of Music from the age of 15. He changed from the violin to composition, working under Charles Villiers Stanford. After completing his degree, he became a professional musician; he was appointed a professor at the Crystal Palace School of Music and began conducting the orchestra at the Croydon Conservatoire.

He later used the name "Samuel Coleridge-Taylor", with a hyphen, said to be following a printer's error. In 1894 Taylor's father was appointed a coroner in the colony of Gambia.

Marriage

In 1899 Coleridge-Taylor married Jessie Walmisley, whom he had met as a fellow student at the Royal College of Music. Six years older than he, Jessie had left the college in 1893. Her parents objected to the marriage because Taylor was of mixed-race parentage, but relented and attended the wedding.

The couple had a son, named Hiawatha (1900–1980) after the poetic figure, and a daughter Gwendolen Avril (1903–1998). Both had careers in music: Hiawatha adapted his father's works. Gwendolen started composing music early in life, and also became a conductor-composer; she used the professional name of Avril Coleridge-Taylor.

Career

By 1896, Coleridge-Taylor was already earning a reputation as a composer. He was later helped by Edward Elgar, who recommended him to the Three Choirs Festival. His "Ballade in A minor" was premiered there. His early work was also guided by the influential music editor and critic August Jaeger of music publisher Novello; he told Elgar that Taylor was "a genius”.

On the strength of Hiawatha's Wedding Feast, which was conducted by Professor Charles Villiers Stanford at its 1898 premiere and proved to be highly popular, Coleridge-Taylor made three tours of the United States in 1904, 1906, and 1910. In the United States, he became increasingly interested in his paternal racial heritage.

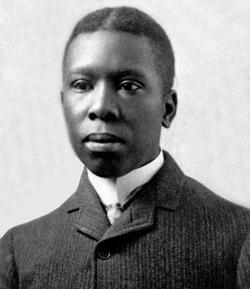

Coleridge-Taylor participated as the youngest delegate at the 1900 First Pan-African Conference held in London, and met leading Americans through this connection, including poet Paul Laurence Dunbar and scholar and activist

W. E. B. Du Bois.

Coleridge-Taylor's father Daniel Taylor was descended from African-American slaves who were freed by the British and evacuated from the colonies at the end of the American War of Independence; some 3,000 of these Black Loyalists were resettled in Nova Scotia. Others were resettled in London and the Caribbean.

In 1792 some 1200 blacks from Nova Scotia chose to leave what they considered a hostile climate and society, and moved to Sierra Leone, which the British had established as a colony for free blacks. The Black Loyalists joined free blacks (some of whom were also African Americans) from London, and were joined by maroons from Jamaica, and slaves liberated at sea from illegal slave ships by the British navy.

At one stage Coleridge-Taylor seriously considered emigrating to the United States, as he was intrigued by his father's family's past there.

In 1904, on his first tour to the United States, Coleridge-Taylor was received by President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House, a rare event in those days for a man of African descent. His music was widely performed and he had great support among African Americans.

Coleridge-Taylor sought to draw from traditional African music and integrate it into the classical tradition, which he considered Johannes Brahms to have done with Hungarian music and Antonín Dvořák with Bohemian music. Having met the African-American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar in London, Taylor set some of his poems to music.

Paul Laurence Dunbar Coleridge at a Festival in Norfolk

A joint recital between Taylor and Dunbar was arranged in London, under the patronage of US Ambassador John Milton Hay. It was organised by Henry Francis Downing, an African-American playwright and London resident. Dunbar and other black people encouraged Coleridge-Taylor to draw from his Sierra Leonean ancestry and the music of the African continent.

Due to his success, Coleridge-Taylor was invited to be one of the judges at music festivals. He was said to be personally shy but was still effective as a conductor.

Composers were not handsomely paid for their music, and they often sold the rights to works outright in order to make immediate income. This caused them to lose the royalties earned by the publishers who had invested in the music distribution through publication.

The popular Hiawatha's Wedding Feast sold hundreds of thousands of copies, but Coleridge-Taylor had sold the music outright for the sum of 15 guineas, so did not benefit directly. He learned to retain his rights and earned royalties for other compositions after achieving wide renown but always struggled financially.

Death

Coleridge-Taylor was 37 when he died of pneumonia. His death is often attributed to the stress of his financial situation. He was buried in Bandon Hill Cemetery, Wallington, Surrey (today in the London Borough of Sutton).

Honours

The inscription on Coleridge-Taylor's carved headstone includes four bars of music from the composer's best-known work, Hiawatha, and a tribute from his close friend, the poet Alfred Noyes, that includes these words:

Too young to die: his great simplicity, his happy courage in an alien world, his gentleness, made all that knew him love him.

King George V granted Jessie Coleridge-Taylor, the young widow, an annual pension of £100, evidence of the high regard in which the composer was held.

In 1912 a memorial concert was held at the Royal Albert Hall and garnered over £1400 for the composer's family.

Family loss Alfred Noyes Royal Albert Hall

After Coleridge-Taylor's death in 1912, musicians were concerned that he and his family had received no royalties from his Song of Hiawatha, which was one of the most successful and popular works written in the previous 50 years. (He had sold the rights early in order to get income.) His case contributed to their formation of the Performing Right Society, an effort to gain revenues for musicians through performance as well as publication and distribution of music.

Coleridge-Taylor's work continued to be popular. He was later championed by conductor Malcolm Sargent. Between 1928 and 1939, Sargent conducted ten seasons of a large costumed ballet version of The Song of Hiawatha at the Royal Albert Hall, performed by the Royal Choral Society (600 to 800 singers) and 200 dancers.

Legacy

Plaques honouring Samuel Coleridge-Taylor in Dagnall Park, Selhurst and South Norwood, United Kingdom.

Coleridge-Taylor's greatest success was undoubtedly his cantata Hiawatha's Wedding Feast, which was widely performed by choral groups in England during Coleridge-Taylor's lifetime and in the decades after his death. Its popularity was rivalled only by the choral standards Handel's Messiah and Mendelssohn's Elijah.

The composer soon followed Hiawatha's Wedding Feast with two other cantatas about Hiawatha, The Death of Minnehaha and Hiawatha's Departure. All three were published together, along with an Overture, as The Song of Hiawatha, Op. 30.

The tremendously popular Hiawatha seasons at the Royal Albert Hall, which continued until 1939, were conducted by Sargent and involved hundreds of choristers, and scenery covering the organ loft. Hiawatha's Wedding Feast is still occasionally revived.

Coleridge-Taylor also composed chamber music, anthems, and the African Dances for violin, among other works. The Petite Suite de Concert is still regularly played. He set one poem by his namesake Samuel Taylor Coleridge, "Kubla Khan”.

Coleridge-Taylor was greatly admired by African Americans; in 1901, a 200-voice African-American chorus was founded in Washington, D.C., named the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Society. He visited the United States three times in the early 1900s, receiving great acclaim, and earned the title "the African Mahler" from the white orchestral musicians in New York in 1910. Public schools were named after him in Louisville, Kentucky, and in Baltimore, Maryland.